Written by Laura Fioretti

Thrust into a decade of compensatory excess, mid-1920s America witnessed the rise of the Moderne aesthetic. Later known as Art Deco, the artistic movement echoed the aspirations of a society reveling in newfound prosperity. With its streamlined symmetry, geometric patterns, and exotic allure, Art Deco embodied everything America aspired to be — opulent, sophisticated, and modern. Becoming increasingly synonymous with the fervour and debauchery of American youth, the decline of Art Deco in the 1930s came as no surprise. As American society’s morals shifted and the extravagant lifestyle of the Jazz Age became untenable, the movement waned. Yet, within the Hollywood scene, Art Deco left an indelible mark that extended beyond its heyday. By bringing the visions of celebrated art directors like Cedric Gibbons and Van Nest Polglase to life, major studios MGM and RKO made Art Deco’s glamorous appeal their trademark.

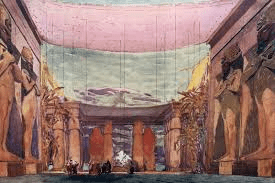

First introduced at the 1925 Parisian International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts, what once was coined « art décoratif » was later abbreviated to the « catch-all » term Art Deco by British art critic Bevis Hillier following a rekindled interest in the movement in the 1960s. Characterised by its symmetrical « classicism, pale stepped-back surfaces, shallow reliefs, and dramatic ornamental flourishes » (Bridget Elliott and Michael Windover 3), Art Deco combined ethnic eclecticism and modernist streamlined shapes in an attempt to divorce itself from the subtleties of its predecessor: Art Nouveau. Much like Expressionism and Cubism, Art Deco was part of a modernist wave of « peinture d’intention » (Hillier 26), where artists sought to represent the essence of the object rather than the object itself. Drawing on the mechanic sentimentalisation of Futurism and the Vorticist rejection of cubist statism, Art Deco prioritised the motion and streamlining of the form. Yet, by embracing the over-the-top embellishments of Ballets Russes stage design, Art Deco impeded itself in its progress towards a « simpler rectilinear form » (Hillier 36), thus making its position within Modernism a matter of contention among theorists. With its rich palette of bold hues, ranging from crimson reds and oranges to opal blues, the Russian Ballet scene became a quintessential source of inspiration for the movement. With its most apparent influence being that of Mesoamerican and Egyptian art, Art Deco borrowed gratuitously, arguably in an exploitative and colonial fashion. From Aztec temples and Mesopotamian ziggurats to Egyptian sphinxes and lotuses, Indigenous motifs became the backbone of Art Deco’s luxurious overtones. Onyx, gold, ochre, jade and obsidian – materials and pigments used to adorn the tomb of Tutankhamun – were adopted to connote the exotic glamour of lost cities.

2. Art Deco and the American Hubris

______________________________________________________

« The contrast between zig-zag and modern can be seen as one between opulence and austerity, luxury and utility, the decorative arts and industrial design, craftsmanship and mass production, or European influence and a quintessentially American interpretation of modernity. »

Hillier and Escritt 79

________________________________________________________

In the aftermath of WWI’s atrocities, the carefree optimism and exuberance of the Roaring Twenties were welcomed with much enthusiasm by the American youth. Indeed, by 1926, under the Coolidge Administration, America saw itself become an economic powerhouse as the total value of shares rose fourfold and unemployment dropped to only 1.9 percent (O’Neal 58). From easy credit obtention to mass advertisement, what ensued was a decade of materialistic greed and self-indulgence. Marking the dawn of a machine age of mass production, Art Deco became the symbol of American exceptionalism and conquest. In the same tradition of emulating European aesthetics since its colonial inception, America adopted the Art Deco movement in an attempt to capture the sophistication and « exclusive ambiance of French high style » (Massey 91). Following their attendance at the 1925 International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts – under the guidance of Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover – American officials and artists were swift to embrace Art Deco’s luxurious exoticism, incorporating the aesthetic in the design of furniture, sculptures, and jewellery, promptly expanding to include the likes of department stores, hotels, theatres, corporate headquarters, film sets and the private home among a wide array of spaces and mediums. Art Deco products brought exclusivity to the masses by merging sophisticated design with affordable and available materials such as steel, glass, and Bakelite.

Bolstered by a culture of mass consumption and changing ideals, Art Deco became increasingly synonymous with the American youth’s hedonistic proclivities. In his book 1920-30s Art Deco, Bevis Hillier highlights the importance of referring to the « Cocktail Age » (60) when discussing late 1920s America in relation to Art Deco, remarking that « a generation starved of superfluidity did not relish stark cubist painting or the ‘purism’ of Ozenfant. They wanted colour, fizz and bubble » (61). While the 18th Amendment sought to restrict alcohol consumption (1920-1933), the Prohibition inadvertently led to the flourishing of illegal establishments. Filled with jazz, abundant drinking, and little restraint, the speakeasy—with its bold geometric patterns and sleek Art Deco wall accents—captured the essence of 1920s American hedonism. Similarly, with her streamlined and boyish figure reminiscent of Art Deco’s fascination with the nimbleness of the female deer (Hillier 70), the flapper became the symbol of America’s changing and loosening morals.

3. Bringing Deco Glamour and the Great White Set to Hollywood

_______________________________________________________

» Details that used to be considered unimportant are now of prime importance in the making of a picture, including details in costuming, fidelity to atmosphere, and everything that goes to make a realistic feature. For that reason, we have specialists at the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio who are experts in their lines. This guarantees that our pictures will be of the highest possible artistic standard. »

Irving Grant Thalberg, Vice President in charge of production at MGM (Courtesy of H. Gutner).

_______________________________________________________

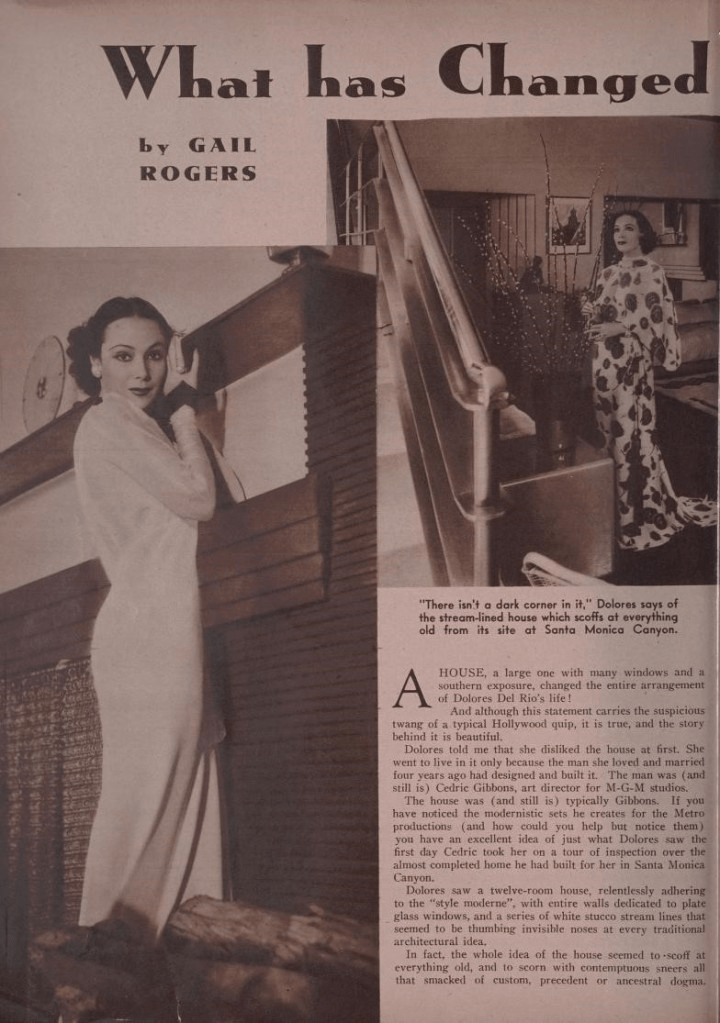

MGM’s Cedric Gibbons

Recognised as one of the most prolific and successful art directors of his time, Cedric Gibbons not only designed the Oscar statuette (1928) but also introduced the Moderne (later known as Art Deco) and its Great White Set to the Hollywood scene. On the merging of Goldwyn Pictures and Metro Picture into MGM in 1924, Gibbons was made to sign a contract securing his name on every American film the studio produced across the span of the following three decades. From The Kiss (1929), starring the quintessential « Moderne » actress Greta Garbo, to the technicolour phenomenon that is The Wizard of Oz (1939), Gibbon’s penchant for Modernist sets allowed MGM to discern and cement itself as the studio of the Glamour.

In 1925, Cedric Gibbons had been thoroughly impressed by the bodies of works exhibited at the International Exhibition of Modern and Industrial Decorative Arts. Tasked with designing the atelier of Russian-born French Artist Romain de Tirtoff, known as Erté – whom MGM co-founder Louis B. Mayer was enamoured with – Gibbons sought to set himself apart by bringing a fresh take on MGM’s style. After introducing three-dimensional furnishings to one-dimensional painted sets, Gibbons’s most notable contribution to the propagation of Art Deco was his use of lighting. Indeed, Gibbons’s use of incandescent, high-key lighting (later copied by Van Nest Polglase and Carroll Clarke in RKO’s Astaire/Rogers musicals) brought about MGM’s « Great White Set » and its characteristic silken gleam « with few shadows to obscure, walls, floors and furnishings » (Gutner 78).

In Harry Beaumont’s Joan Crawford star vehicle Our Dancing Daughters (1928), Gibbons’s use of Art Deco architecture and lighting are particularly significant in delineating the film’s tensions between the liberated, progressive ideals of the Jazz Age and the conservative, traditional values of the past. In the film, Joan Crawford plays Diana Medford, nicknamed « Dangerous Diana », a peppy, charleston dancing and cocktail-drinking flapper who embodies the free-spirited ethos of the roaring twenties. With her « snappy parents » and their modern leniencies, Diana is first presented to the viewer within the setting of their ultra-modern home. Characterised by its streamlined furniture, black statues and terrazzo tiles « devoid of rugs and carpeting » (Gutner 79), curvilinear archways, geometric patterns, and bared walls with the occasional golden highlight, the Medford home—brightly lit by Gibbons’s characteristic use of high key lighting— parallels Diana’s upbringing and her parents’ quintessentially modern outlook. Diana’s « up-to-the-minute » home (Gutner 79) is juxtaposed against the Edwardian-style home of Dorothy Sebastian’s Beatrice. With its old-fashioned damask and floral patterns, ornately carved furniture, carpeted flooring and exaggerated chandeliers, the house reflects her parents’ outdated morales. In the same vein, the hotel apartment where Ann (Anita Page) and her mother stay, with its gaudy and light-absorbing curtains, emphasises the exclusive quality of Art Deco architecture as a signifier of wealth

RKO’s Van Nest Polglese and Carroll Clarke

From Top Hat (1935) to Swing Time (1936), Art Director Van Nest Polglese and Associate Art Director Carroll Clarke left an indelible mark on RKO Astaire-Roger musicals with their lavish Art Deco set designs and their own Gibbons-inspired Great White Set. In Mark Sandrich’s Top Hat (1935), Fred Astaire’s Jerry Travers awaits Horace Hardwick (Edward Everett Horton) in an Edwardian-style gentleman’s club adorned with dense curtains, damask accent armchairs, and carpeted flooring. The set and its oppressive silence mirror the old-fashioned rigidity of the middle-aged men who occupy it. A clear generational divide is presented, with Jerry’s youthful energy clashing against the men’s outdated notions of decorum. When Jerry joins Horace in his luxury hotel room, Horace’s upper social status is made apparent through its hyper-modern furnishings. As seen in Gibbons’s contribution to Edmund Goulding’s Grand Hotel (1932), the luxury hotel is a recurring backdrop to the Art Deco style. With a heavy-handed use of incandescent light (high-key lighting) and streamlined design, the room epitomizes the notion of the Great White Set. Moreover, when Dale Tremont, played by Ginger Rogers, is awakened by Jerry’s tap dancing, the camera travels vertically from Horace’s room, with its high ceilings and streamlined grandeur, to Dale’s plushly upholstered bed, framed by sheer curtains. In the same trend, kickstarted by the 1930s Hays Code, women’s beds were either raised on plinths (Massey 71) or, as the likes of Top Hat, a veil was hung on an overhead rod to separate and protect the private feminine space from the salacious male gaze.

The Decline of Art Deco

By the end of the 1930s, Art Deco’s decorative exuberance gave way to a more restrained form of Modernist linearity, Streamline Moderne. Disillusioned by the onset of WWII and the financial devastation that the Great Depression had left in its wake, the American people no longer gravitated towards Art Deco’s lavish appeal. The excesses and indulgences synonymous with Art Deco seemed out of place and out of touch with the world’s climate of hardship and uncertainty. In fact, in the book Art Deco 1910-1939 (2003), Charlotte and Tim Benton assert that « Art Deco was definitively killed off by the Second World War, or rather by the mentality of service, sacrifice and social reform engendered by the mentality of that war » (427). Although Art Deco was not fully recognized as a distinct movement until the 1960s, its glamorous appeal persisted well into mid-century set design, evolving from its exuberant ornateness to cleaner, more straightforward lines.

Works Cited:

Benton, Charlotte, Tim Benton, Ghislaine Wood, editors. Art Deco 1910-1939. Bulfinch Press/AOL Time Warner Book Group, 2003

Charles, Victoria. Art History Art Deco. Parkstone International, New York, 2024.

Elliott, Bridget, and Michael Windover. The Routledge Companion to Art Deco. Routledge, Oxford, 2019.

Friedman, Marilyn F. « The United States and the 1925 Paris Exposition: Opportunity Lost and Found. » Studies in the Decorative Arts, vol. 13, no. 1, 2005, pp. 94–119.

Gutner, Howard. MGM Style: Cedric Gibbons and the Art of the Golden Age of Hollywood. Lyons Press, 2019.

Hillier, Bevis. Art Deco of the 20s and 30s. Schocken Books, 1985.

Hillier, Bevis, and Stephen Escritt. Art Deco Style. Phaidon, 1997.

Lindop, Edmund. America in the 1920s. Twenty-First Century Books, 2007.

Massey, Anne. Hollywood Beyond the Screen: Design and Material Culture. 1st ed., Bloomsbury Academic, 2000.

O’Neal, Michael. America in the 1920s. Facts On File, 2006.

Ramirez, Juan Antonio. Architecture for the Screen: A Critical Study of Set Design in Hollywood’s Golden Age. McFarland & Company, Inc., 2004.

Todd, Drew. « Dandyism and Masculinity in Art Deco Hollywood. » The Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 32, no. 4, 2005, pp. 168-181

Grand Hotel. Directed by Edmund Goulding, performances by Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, and Joan Crawford, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1932.

Our Dancing Daughters. Directed by Harry Beaumont, performances by Joan Crawford, Anita Page, and John Mack Brown, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1928.

Top Hat. Directed by Mark Sandrich, performances by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, RKO Radio Pictures, 1935.

Images Cited:

1. Bakst, Leon. Set Design for a Ballets Russes Production of Cleopatra. 1909. Museum of Modern Art, New York. Hulton Fine Art Collection, Getty Images. Image No. 463913161.

2. Lewis, Frederic. Crown of the Chrysler Building. 1 Jan. 1930. Archive Photos, Getty Images. Image No. 50895776.

3. « Art Director Cedric Gibbons in His Office. » John Springer Collection, Corbis Historical, Getty Images, 1 Jan. 1920, Image No. 526873976.

4. Movie Mirror. Vol. 6, no. 6, 1929, p. 480. Lantern Media History Project, lantern.mediahist.org/catalog/moviemirrorvol6d06unse_0480.

5. Our Dancing Daughters. Directed by Harry Beaumont, performances by Joan Crawford, Anita Page, and John Mack Brown, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1928.

6. Top Hat. Directed by Mark Sandrich, performances by Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers, RKO Radio Pictures, 1935.